What are Proteasomes

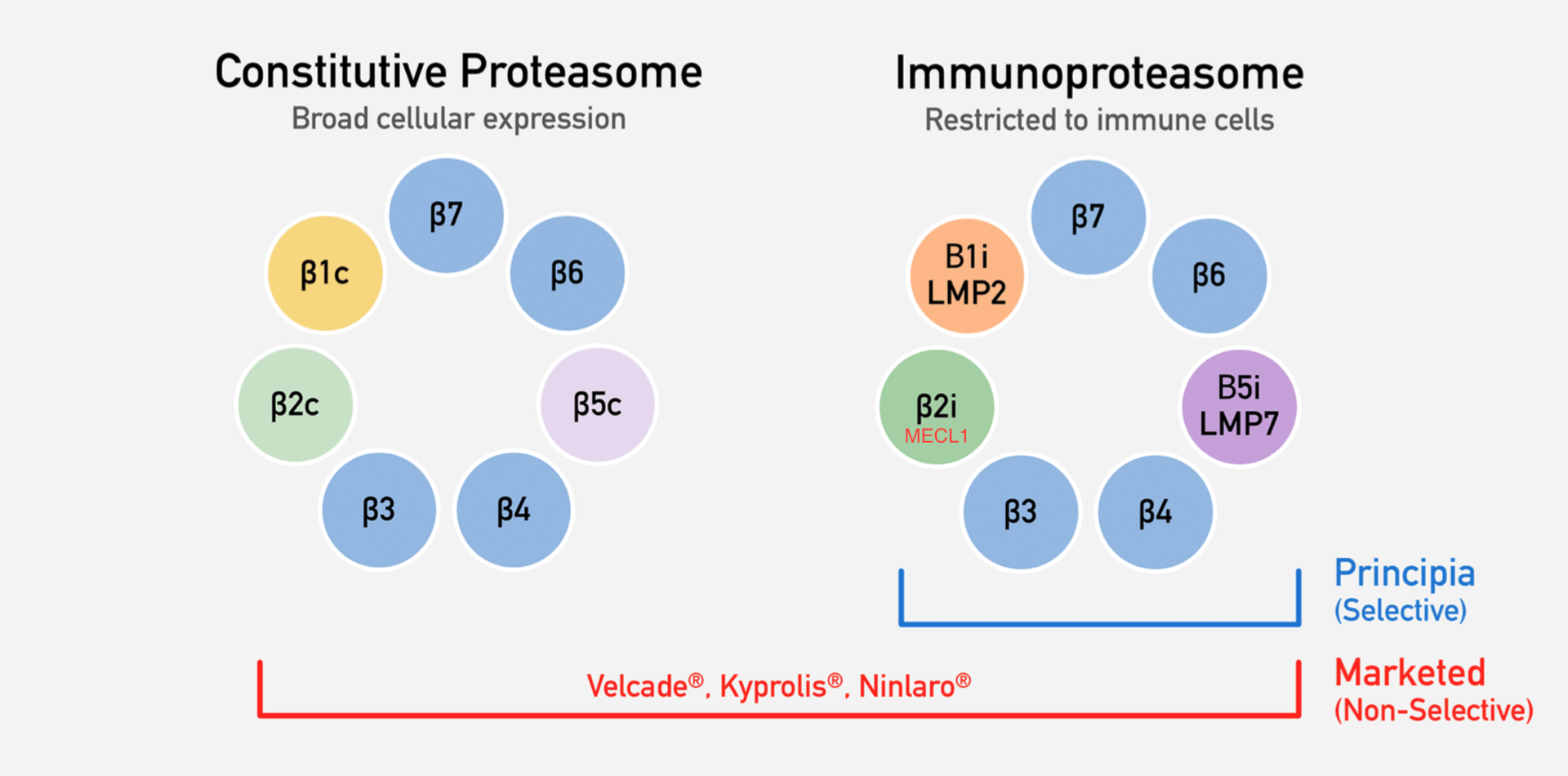

The proteasome is a protein complex that degrades unneeded or damaged proteins, and can be found in all eukaryotic cells. There are several subtypes of proteasome. The constitutive proteasome is found in all tissues, while the immunoproteasome is found in monocytes, lymphocytes, and in non-immune cells during times of inflammation (Cromm 2017). The important proteolytic subunits in the constitutive proteasome are the B1c, B2c, and B5c subunits. In the immunoproteasome, those subunits are swapped out with similar ones that process antigens in slightly different methods, increasing the quantity and diversity of MHC I presentation (Basler 2012). Thus, the immunoproteasome plays an important role in pro-inflammatory cytokine response. For simplicity, I’ll refer to the immunoproteasome subunits as B1i, B2i, and B5i, but the alternative subunits names are in the diagram below (Principia Bio corporate presentation).

Proteasome Inhibitors

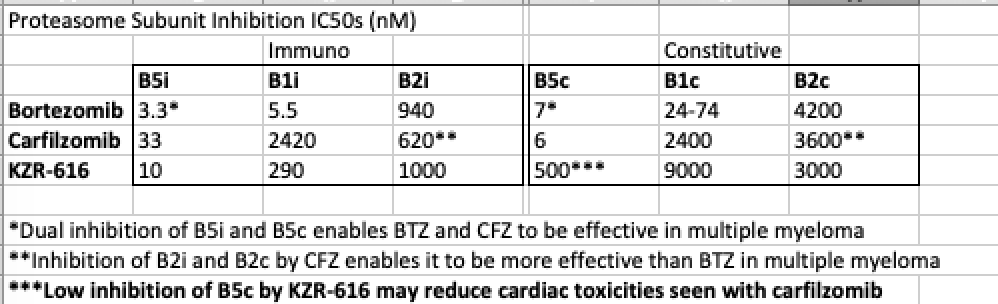

Current proteasome inhibitors on the market include bortezomib (Takeda) and carfilzomib (AMGN), and inhibit the B5c and B5i subunits. This causes cells to accumulate too many unwanted proteins in a response termed UPR (unfolded protein response), which causes cell death (Besse 2019). However, it’s important to note that both the B5c and B5i subunits need to be targeted for cytotoxicity, as immunoproteasome-selective inhibitors do not achieve cell death.

Interestingly, most proteasome inhibitors begin to lose specificity at higher dosages. At higher doses, bortezomib begins to inhibit the B1c/i subunits, while carfilzomib begins to inhibit the B2c/i subunits (Kraus 2015). Ironically, this is to their benefit, as it has been shown that inhibition of B5c/i subunits alone is not optimal for cytotoxicity in multiple myeloma (Besse 2019). It has also been shown in mouse models that additional B2c/i inhibition in combination with a B5c/i inhibitor overcomes bortezomib resistance (Kraus 2015). This is just a glimpse of the intricate interplay between proteasome subunits.

Kezar is developing KZR-616, an inhibitor that does not target the constitutive subunits. Therefore, KZR-616 will not induce cytotoxicity in multiple myeloma like its predecessors. If immunoproteasome-selective inhibitors won’t work in cancer, where can it be used? Instead of killing cells, Kezar hopes that inhibiting immunoproteasomes will modulate the heavy influx of cytokines seen in autoimmune diseases. Kezar’s first indication is in SLE (systemic lupus erythematosus) and lupus nephritis.

Bortezomib Use in Lupus

SLE is an autoimmune disease characterized by the production of autoantibodies that attack the healthy tissues, resulting in inflammation to the joints and other organs. Lupus nephritis occurs when this involves the kidneys. Several autoimmune diseases, such as SLE, are associated with the up-regulation of the B5i immunoproteasome subunit (Castellano 2015). Since bortezomib affects the B5i subunit, it’s logical to think that it would be effective in the treatment of SLE.

In two separate refractory SLE studies of 12 patients (Alexander 2014) and 5 patients (Zhang 2017), bortezomib was seen to be effective after 2-4 cycles, when co-administered with steroids. Anti-dsDNA and proteinuria levels declined by over 60%, indicating several complete and partial responses, with durable remissions lasting over 2 years. Bortezomib also rapidly reduced SLEDAI scores (a measure of severity of SLE) after just one treatment cycle (21 days). Interestingly, in the 12 patient study, 7 patients were re-sensitized to other immunosuppressant regimens (Alexander 2014).

Toxicity Problems

Though there are good signs of clinical efficacy, chronic use of proteasome inhibitors is largely prevented by toxicities. Bortezomib use commonly encounters peripheral neuropathy (related to off-target proteases), as well as cardiac and pulmonary toxicity, and thrombocytopenia (Verbrugge 2015). In a long-term trial for bortezomib in SLE, 7/8 patients failed to complete the full protocol due to AEs (Ishii 2018). Furthermore, in mouse models, bortezomib in SLE showed lower survival in mice with higher disease activity due to toxicities (Ikeda 2017). Carfilzomib also encounters severe cardiac toxicities at high doses. Heart tissue contains significantly lower active proteasome per protein than other organs, which makes it vulnerable to high B5c inhibition (Besse 2019).

KZR-616

KZR-616 is an analogue of ONX-0914 (Proteolix/Onyx/AMGN), which is a semi-specific B5i inhibitor, with additional inhibition of B1i at higher doses. Comparatively to bortezomib or carfilzomib, it has very low inhibition of the B5c subunit (see IC50s in table above). As you would expect with a proposed mechanism to reduce pro-inflammatory cytokines, KZR-616 has pre-clinically shown to prevent B-cell differentiation, block production of IFN-a and TNF-a, and lower levels of IL-6 and IL-23, highlighting its potential in autoimmune disease treatment (Muchamuel 2009). In mouse models of SLE, this translates to complete resolution of proteinuria, significant reductions in anti-dsDNA, and the complete halt in disease progression, even 8 weeks after treatment discontinuation (Muchamuel 2018). In a Phase 1 healthy volunteer study, KZR-616 showed potent B5i (>80%) and B1i subunit (>40%) knockdown, while mostly sparing the B5c subunit (<40%). As hoped, KZR-616 has seen none of the usual toxicities associated with bortezomib and carfilzomib up to a 45mg dose. Signs of systemic drug reactions similar to carfilzomib administration were starting to be seen at 60mg (Lickliter 2017). A Phase 1b study in lupus nephritis patients at 45mg is set to read out in 1H19.

Remaining Questions

While KZR-616, a B5i and B1i subunit inhibitor seems promising in SLE, it’s important to note that not all autoimmune disease behave the same way. For example, in experimental colitis, it was shown the both B5i and B1i subunits need to be inhibited for disease attenuation (Basler 2014), while patients with Sjörgsen’s suffer from dysregulation and deficiency of the B1i subunit (Kraus 2006). Thus, KZR-616 would have different effects in both diseases. It may be a better approach to use multiple specific subunit inhibitors, and titrating to the proper levels of inhibition. It was seen in graft-vs-host disease that inhibition of B5i reduces GVHD, but higher doses reduced selectivity and shortened survival times in mice (Zilbenberg 2015). Finally, in genetically engineered B5i-deficient mice, a compensatory mechanism upregulated the constitutive subunit B5c in these immunoproteasomes (Nathan 2013). While this hasn’t been seen in normal mice with subunit inhibition, this compensatory mechanism would logically disrupt the efficacy of a B5i specific inhibitor.

Conclusion

Overall, the attempt to make a safer, more potent proteasome inhibitor are intriguing. However, it will be important to fully understand each disease indication, due to the intricate balance between proteasome subunits. So far, the inhibition profile of KZR-616 is promising, and other mechanisms aside from immunosuppressants are desperately needed in the treatment of SLE. The off-label use of bortezomib gives me more confidence in the potential of KZR-616, and I look forward to the first efficacy results.